Survival Curves: The A/B Testing Tool Most Teams Ignore

Why “no lift” often means “you’re not looking closely enough”

Most A/B tests end the same way.

A slide.

One number.

A conclusion that sounds like:

“Conversion was flat. No meaningful difference.”

If you’ve been running experiments for more than a couple of years, you know that conclusion is often wrong. Not technically wrong. Just incomplete.

Some of the most important behavior changes never show up in a final conversion rate. They show up in how long users hesitate, wait, or drop out before anything happens.

That’s what survival curves are good at surfacing.

The blind spot in most experimentation programs

Traditional A/B testing answers a narrow question:

Did Variant B convert more users than Control?

That works fine when decisions are instant. It breaks down when users:

Hesitate

Compare options

Leave and come back

Drop off mid-flow

Delay action across sessions

Most real product changes affect decision timing, not just outcomes.

If all you measure is the endpoint, you miss the behavior change entirely.

What a survival curve actually shows

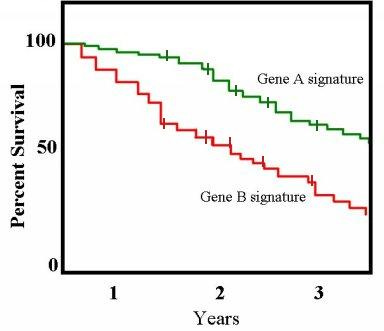

A survival curve plots the percentage of users who have not yet experienced a defined event at each point in time.

The event can be anything, but it must be precise:

Conversion

Funnel abandonment

Churn

First meaningful action

The mechanics are simple:

The curve starts at 100 percent

It stays flat when nothing happens

It steps downward when users hit the event

It never goes up

Each curve represents a cohort, usually control vs test.

(Image Source: wikipedia.org)

Despite the name, there’s nothing morbid about it. It’s just borrowed statistical language.

How to read survival curves without overcomplicating it

Two rules cover most interpretations:

A higher curve means more users have not yet hit the event

A steeper drop means the event is happening faster

Whether “faster” is good or bad depends entirely on the event.

If the event is conversion:

Faster can be good

If the event is churn or abandonment:

Faster is bad

What matters most is where and how the curves separate.

Patterns I see regularly in real tests:

Early separation, then convergence

The test changed hesitation, not intentTest drops faster early

Reduced friction or clearer decision-makingTest stays higher longer

Added cognitive load or uncertaintyCurves separate and never reunite

Strong behavioral difference, even if final conversion is flat

This is usually where product teams say, “Something feels off,” while dashboards say everything is fine.

Why conversion rate alone hides these effects

Two variants can end with the same conversion rate and still deliver very different experiences.

Example I’ve seen more times than I can count:

Control converts slowly but steadily

Test converts faster early, then levels off

Final conversion is identical.

But users:

Decide sooner

Need fewer sessions

Spend less time stuck

Reach value faster

If you only report conversion rate, the test looks like a wash.

If you look at survival curves, you see a meaningful behavioral shift.

The technical reason analysts care about this

At the end of any experiment, a large share of users:

Haven’t converted yet

Haven’t churned yet

Are still mid-flow

Those users aren’t failures. They’re unfinished.

Standard metrics quietly mishandle this. Survival analysis doesn’t. It treats those users as censored rather than misclassified.

That’s especially important in:

Long onboarding flows

Subscription products

High-consideration purchases

Fixed-length experiments

One important caveat: survival analysis assumes censoring isn’t systematically tied to the event. In product data, that’s not always true. You still need judgment.

A quick note on the statistics

Most survival curves in experimentation use:

Kaplan–Meier estimation to draw the curves

Log-rank tests to compare them

The log-rank test works best when the curves don’t cross too much. If they do, that’s not a failure. It’s a signal that the effect changes over time and needs closer inspection.

The key point isn’t the test itself. It’s the question being asked:

Not “Did conversion go up?”

But “Did the timing of user behavior change?”

Those are different questions.

When survival curves are worth using

I don’t recommend them for every experiment.

They’re most useful when:

Users can pause, hesitate, or abandon

The flow has multiple steps

The test changes clarity, trust, or complexity

Conversion rate alone feels unsatisfying

They add little value when:

The action is instantaneous

Traffic is extremely low

Timing is irrelevant to the decision

A simple rule I use:

If users can think, timing matters.

If timing matters, survival curves help.

Why this matters as programs mature

Early experimentation programs fail on statistics.

Mature programs fail on interpretation.

Teams ship:

Extra explanation that slows decisions

Friction that looks “safe” but adds drag

UX changes that increase hesitation

And the dashboard says everything is fine.

Survival curves expose that gap. Not perfectly. But far better than a single end-state metric.

The takeaway

Survival curves don’t replace conversion rate. They complete it.

Conversion tells you what happened.

Survival curves show how it happened over time.

If you’ve ever felt uneasy shipping a “flat” test, this is probably why.